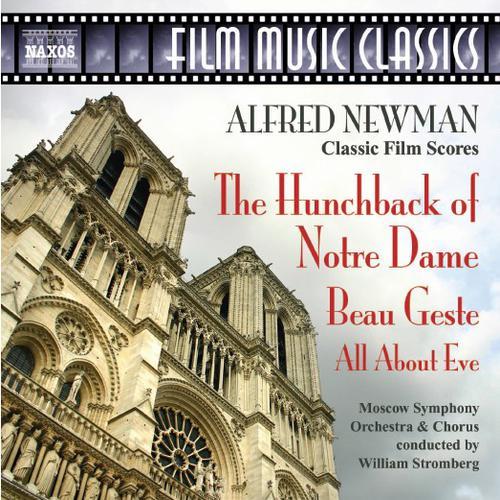

Newman: Hunchback Of Notre Dame (The) Beau Geste All About Eve

Alfred Newman (1901–1970)

Music for the films

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939)

Score restoration/ reconstruction by John Morgan

Beau Geste (1939)

Score reconstruction by William Stromberg

All About Eve (Suite) (1950)

Of all the talented, groundbreaking composers who busied themselves during Hollywood's golden age, Alfred Newman was perhaps the most powerful, most influential and certainly most insightful. Yet, for all the praise lavished on his vast work as a composer, conductor and administrator, Newman has received scant attention in the recent spate of film-music re-recordings. At least one reason involves the films he scored. Many were top-flight productions in their day, but they now lack the enthusiastic, faithful followings boasted by Warner Bros.' Errol Flynn swashbucklers and Humphrey Bogart film-noir classics, Universal's vintage monster movies and the special effects-packed Ray Harryhausen spectaculars. "What attracts so many people isn't just the music but the film itself," conductor and composer Fred Steiner, foremost expert on Newman's music, lamented in 1996, more than a quarter-century after Newman's death. "Some of the films Alfred Newman scored then don't have drawing power today. Wuthering Heights may be OK, but whoever heard of Beloved Enemy? It's not like the popularity of The Adventures of Robin Hood or Gone with the Wind. Of course, then again, the last thing we all need is another re-recording of Gone with the Wind!"

One can also argue that Alfred Newman's wonderful scores have been handicapped by the very fact he so effectively set the tone for much film music of the 1940s and 1950s — literally and figuratively. Although he wrote in a richly romantic idiom that owes much to Richard Strauss, Newman shaped it in such a successful manner that many other composers in Hollywood quietly adopted similar stylistic tendencies (though precious few succeeded in furnishing scores that functioned as well as his). Today long-dead film composers with particularly individualistic styles — Erich Korngold, Bernard Herrmann, Dimitri Tiomkin and Max Steiner spring to mind — cannot help standing out against the standard so firmly set by Newman from his perch as music director at 20th Century-Fox. This may well be why their music — so different from that Hollywood norm — is also given more attention today. In any case, the neglect Newman's film music experiences is unwarranted, especially considering such soaring, swashbuckling scores as Captain from Castile (1947) and Prince of Foxes (1949), religious dramas such as The Song of Bernadette (1943) and The Robe (1953) and gargantuan epics such as The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939).

Considering the huge number of films Newman scored and the quality he sustained till his death in 1970, it's remarkable he approached composing with such reluctance. Yet he did. "Newman worked on a total of 225 films and toward the end admitted that it was too much to have done," author, producer and long-time Newman friend Tony Thomas wrote in Film Score: The View from the Podium. "As a conductor, he was probably the finest ever to work in films. It was what he most loved to do, and the many who played under his baton claim that had circumstances been different, he would most likely have been an outstanding symphonic conductor. Despite his talent as a composer, he did not enjoy the work of sitting and inventing music. A most gregarious man by nature, the loneliness of composing disturbed him, and he admitted he often sat for hours looking at blank music paper before being able to write a note." In an interview on occasion of the recording at hand, veteran film-music orchestrator Arthur Morton echoed this insight concerning Newman's immense talents at the podium, though he also outlined certain preferences: "He was reluctant to do anything outside the studio. When he went to conduct at the Hollywood Bowl, I remember he was a nervous wreck. But inside the studio, in front of an orchestra — and, let's face it, 20th Century-Fox had the best — he was an absolute master. He loved conducting and he was good at it."

Despite his admitted dread of composing, and despite the fact he had no particular interest in films when he first came to Hollywood, Alfred Newman's sense of the dramatic was unerring. In scoring the brooding, windswept world of Wuthering Heights (1939), he furnished nearly 75 minutes of music for the 103-minute film. Similarly, for the sweeping adventure of Captain from Castile, he again decided to furnish a full score, from which he drew for one of the earliest soundtrack albums produced (and one, incidentally, that proved quite respectable in sales). On the other hand, for Grapes of Wrath (1940), Newman sized up the film's gritty Americana in the face of bleak conditions and was lean and raw-boned in his scoring, limiting what music he did furnish to folkish elements. Later, for Twelve O'Clock High (1949), he again considered the grim austerity and dismal mood of the film's situations — an American officer dealing with depression and despair among World War II bomber crews — and shrewdly opted to score as little as possible. (One of the few sequences was a reworking of friend and colleague Hugo Friedhofer's effectively nightmarish bomber music from The Best Years of Our Lives just three years earlier.)

Even when Alfred Newman was sparing in his scoring of a film, the efforts were frequently memorable. No film proves this better than All About Eve (1950), a classic about a middle-aged, somewhat insecure actress, her deceitful, conniving protégée and New York's gossipy, intrigue-filled theatre world. Newman's decision to limit his scoring is understandable enough. With crisp scriptwriting and taut direction, both by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, and wonderful ensemble acting from a spunky cast that included Bette Davis, Anne Baxter, Gary Merrill, Hugh Marlowe and, as a newspaper critic with a sharp pen and tongue to match, George Sanders, anything more from 20th Century-Fox's music department might have been overkill. (It is certainly a lesson the film's Margo Channing could have heeded in the celebrated party scene where she demands her pianist perform Liszt's Liebestraum No. 3 repeatedly, much to her guests' dismay.) Brief though Newman's All About Eve score is, the main title is unforgettable, a dynamic flourish in the brass unleashing a bustling theme that conveys all the excitement and magic of New York's frantic theatre world, so much the obsession of the title character. (Incidentally, the main title's entry neatly fills in for Newman's famous 20th Century-Fox fanfare, which usually preceded the studio's films.) In the brief suite at hand, the key theme for Anne Baxter's Eve Harrington, and the theatre scene that drives her so, continues on in different guises, including a seemingly tender, innocent one. But its climactic appearance — coming in the film just after Eve has found success and, along with it, cynicism and despair — is just as memorable, reflecting the envy, lust and intoxicating allure that characterize the theatre limelight as well as a hint of the jarring darkness just beyond it.

By 1950, Alfred Newman was at the height of his career, not just as a composer and conductor but as an administrator who had gained the trust of studio executives and the composers those same executives might have otherwise been reluctant to employ. He had cleared the way for such talented composers as David Raksin, Hugo Friedhofer and the irascible Bernard Herrmann (and, in doing so, indirectly gave the world such remarkable scores as Raksin's Laura, Friedhofer's The Best Years of Our Lives and Herrmann's The Ghost and Mrs. Muir). Herrmann's career as a film composer might have ended in the 1940s without the faith Newman continued to show in him. Newman had Darryl F. Zanuck's ear at Fox and, because of that, Herrmann wound up scoring more pictures for that studio than he did for any other. Fred Steiner, who came to know Newman in the 1950s and later worked with him on the epic The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), said Newman's immense talent and ethic for hard work aided him in his job, but so did his personality. "He was very short and very dynamic, with a surprisingly deep voice for someone of his physical stature," Steiner recalled. "He was very much in command and a leader. In music, you can tell pretty quick when a guy knows his onions — and he did. And yet, he was always a very affable guy."

No one would have been more surprised at Newman's career in 1950 than Newman himself just twenty years earlier, when the 29-year-old Connecticut Yankee — the product of an impoverished family and the oldest of ten children — left conducting duties on Broadway for what he assumed would be a temporary job in Hollywood — serving as music director for Irving Berlin on the film Reaching for the Moon. At the time Newman had no serious interest in film music and eagerly anticipated returning to New York once his well-paying, three-month stint was done. But like many others visiting Hollywood, the money and opportunities quickly intrigued him. "I don't think any of them knew what they were doing or what they were getting into," Fred Steiner said of composers in Hollywood at the time. "Musicals as films were especially popular then, and studios were grinding them out and were bringing composers and songwriters out in droves. So when Newman came out, he came out to do a musical film, though they later dropped all the songs in the film but one!"

Today film-music scholars place Newman, along with Korngold and Max Steiner, in the triumvirate of great golden-age film composers emphasizing a heady symphonic style. What makes Newman's inclusion all the more remarkable is that, compared to Korngold and Steiner, he had little advanced schooling in composition, only his innate instincts in music to aid him. Apparently it was enough. In 1931, he furnished his first truly original score for the film Street Scene, the main theme of which proved so effective he re-used it in subsequent films. By the mid-1930s, with Hollywood's film music still evolving, Newman had already made his mark as a reliable and imaginative composer, and in 1939, then working diligently at various studios, he produced several significant scores, four of which received Academy Award nominations — The Hunchback of Notre Dame, They Shall Have Music, The Rains Came and Wuthering Heights. Ironically, a functional but not terribly imaginative score, written for the western Stagecoach, triumphed over them all that year. Newman, ever displaying faith in his colleagues, voiced no personal disappointment. He later remarked he thought the honor should have gone to Max Steiner for Gone with the Wind.

If there was room for one more Academy Award nomination in 1939, Newman's rousing score for Paramount's Beau Geste certainly deserved the spot. Director William Wellman's desert drama about three brothers (Gary Cooper, Robert Preston and Ray Milland) and their undying devotion to one another and family may be convoluted, chatty, even corny at times, but it also boasts enough assets to certify it as a genuine classic. For one thing, there is Brian Donlevy's zesty performance as evil Sergeant Markoff of the Foreign Legion, forever uttering some threat to his men — and always punctuating it with a snarling, devilish, "I promise you!" Secondly, there's wide-eyed J. Carrol Naish as the sergeant's simple-minded lackey. Who can forget Naish being shot off the guard tower in the final Arab attack, his crazed, hyena-like laugh following him all the way down? And then there's Newman's vividly imaginative music, alternately carefree, ominous and haunting, either allowing for the more far-fetched elements of P.C. Wren's novel to meld more smoothly or whipping up enthusiasm for the characters so effectively one doesn't worry about the storyline's more outrageous twists.

The main title offers three of the motifs right off — a grim mention of the motif representing the Foreign Legion, then a jaunty, full-blooded theme springing to life largely through the strings and representing the Geste brothers, their high spirits and their love of adventure. Then comes an exotic motif from the oboe conveying the dangers of the Sahara Desert and the warlike Arabs who roam it, while an alto flute at the same time mystically foretells how the Legion's destiny is hopelessly wrapped up in this hostile and unforgiving land. The main title is just enough evidence of excitement and faraway settings to keep most viewers in place for the film's more leisurely paced first part, itself merrily buoyed by Newman's music, as heard in the cue The Early Years. In it, we receive a strutting, seagoing version of the Geste brothers theme, scored for the sequence when the brothers, as boys, play high-adventure games and even mount a "Viking funeral" (during which the Geste theme is quite solemnly intoned by the woodwinds).

Other moments of Newman's fertile imagination surface readily, including the joyfully frantic Chasing a Mouse, in which two of the brothers — now grown — playfully pursue an English mouse, only to decide on mercy for the rodent. In addition, an eerie motif, coloured by flutes and celeste with vibraphone, plus the strings briefly playing harmonics, appears in connection with the family's prized sapphire, whose mysterious theft sends the Geste brothers from their comfortable estate home into the barren desert.

Newman makes frequent use of most of these motifs, always in clever ways. The martial motif for the Foreign Legion is heard in its most defiant form in the cue March Out (and, though not included in the suite at hand, is heard in especially grave and deliberate fashion when the young and decent lieutenant who commands the desert outpost tragically succumbs to fever — a passage rendered all the more effective when it suddenly stops, signifying through its silence the officer's death). Elsewhere the upbeat theme for the Geste brothers appears in numerous variations — sometimes tenderly to signify their concern for one another, sometimes heroically, as in those scenes when they and other soldiers desperately defend Fort Zinderneuf, the rollicking theme locked in a death-grip with the aforementioned Arab motif, by now more frantic and boasting far greater symphonic forces. The Foreign Legion's theme is also caught up in all of this action, with everything rushing together in the madness of battle. Most searing of all, though, are those portions of the score conveying death as it quickly spreads throughout the doomed fort, ultimately captured in the cue A Viking's Funeral, with the other-worldly, high-pitched female chorus, the heavy droning of the lower brass, and, finally, a brief trumpet-call atop it all signifying the obligations of a soldier of the Foreign Legion — even a dead one. Coupled with the stark images of Fort Zinderneuf — soldiers' bodies propped up to appear as if they're still ready for another Arab attack — these passages are perhaps the most powerful of all in Newman's Beau Geste. The intermingling again of the oboe and alto flute, signifying the ever-insurmountable dangers of the Sahara and the Legion's mission, now reminds one and all of a destiny fulfilled.

The grand score for RKO's production of The Hunchback of Notre Dame has garnered increasing attention through the years, not just because of its thrilling variety and richness of invention but also because it was produced during a busy period when Alfred Newman was working on several film scores. The Hunchback score arose from a mammoth challenge. The studio sank a fortune into its remake of Victor Hugo's sprawling novel about Quasimodo, the deaf, misshapen bell-ringer of Notre Dame cathedral, and his doomed love for gypsy dancer Esmeralda. On an eighty-acre ranch in the San Fernando Valley, a Life reporter of the time marveled at a 190-foot replica of the famed cathedral, complete with towers, vaults, bells, stained-glass windows and, most important of all, various gargoyles. Below all of this the studio erected an entire medieval village, complete with countless crates of celery to represent the garbage of a sprawling city. Even sets from Universal's famed 1923 version of the novel were brought in for the new production, though there the similarity ended. With tall, imposing, white-gloved German director William Dieterle at the helm and British actor Charles Laughton tackling the title role — and doing plenty of real-life suffering under weighty, confining makeup during filming in 100-degree weather — the film promised much. Studio publicists heightened anticipation, too, by refusing to release any pictures of Laughton in his Quasimodo makeup. They were likely overjoyed, too, when Life printed a photograph of just that, "smuggled" past the studio's own uniformed gargoyles.

With its haunting cathedral interiors, lonely bell-tower and crammed Paris streets full of thieves, charlatans, celebrants and dreamers, Dieterle's Hunchback of Notre Dame demanded a widely ranging score reflecting not only the sacred and the profane but the dark anxiety of the times and fleeting hopes of better things to come. To quote Charles Higham in his book, Charles Laughton: An Intimate Biography (Doubleday, 1976), the film pivoted heavily on its inspired score and Laughton's own stunning expressiveness: "This is an operetta without songs, accompanied by composer Alfred Newman's crashing chords and celestial choirs, suggesting menace or exaltation. Under the circumstances, Charles' achievement is nothing short of astonishing. With only a handful of lines of dialogue and a succession of action scenes in which he is crowned king of the grotesques, accused of seducing Esmeralda and whipped on the wheel, seen ringing the bells and rescuing the unhappy girl from the hangman's noose, he somehow creates a character." Nowhere is this more true than in the sequence where gypsy dancer Esmeralda sees Quasimodo in torment and brings "water and a little pity" to the whipped and tightly bound beast on the wheel — a scene all the more moving with Newman's shimmeringly beautiful version of Esmeralda's theme. Thanks to the composer's typically warm string-writing and Laughton's moving portrayal, the scene ranks as one of the most powerful in film.

"It's a truly remarkable score, especially in regard to the character of the themes," Fred Steiner remarked of the Hunchback music, shortly after much of the score was performed by the Moscow Symphony Orchestra in 1996 for the present recording. "The great thing about the themes for the hunchback, Esmeralda, the young soldier she falls for and the poet Gringoire is that they all fit their personalities so well. One might say of the theme for the hunchback that it's mickey-mousing, musically simulating the way he drags one leg behind him — but it's so much more than that, it's real music." Indeed, Newman is not stingy in trotting out motifs and themes for various characters in Hunchback, and he parades them forth early on. The gorgeous motif for Esmeralda (nineteen-year-old Maureen O'Hara) springs forth, aptly, from the red-blooded music beginning the cue The Gypsies, though it no sooner makes its passionate presence known than violent chords clear the way for a hulking, awkward-sounding motif from the orchestra's bowels for Notre Dame's hideously deformed bell-ringer. (This accompanies a scene in which a woman runs screaming through the streets, panic-stricken after Quasimodo crosses her path.) Shortly thereafter, in the midst of the unrestrained merriment of the Festival of Fools gripping all Paris, including the old-fashioned royalty viewing it all, the motif for the idealistic poet Gringoire (Edmond O'Brien in his film début) is first sounded in the strings toward the end of the cue In the King's Box — earnest, noble and unhindered by the wonderfully biting tonalities heard moments earlier in The Festival and, of course, far more progressive than the period music representing all the King's men.

Other memorable motifs are served up as the film progresses, including that for Frollo (Sir Cedric Hardwicke), the king's stern high justice and Quasimodo's protector. Frollo's motif first surfaces on the alto flute in the cue Thank You Mother of God — seemingly gentle and refined and orderly on initial hearing, yet just odd enough to signal the fatal flaws in his personality that precipitate so much of the trouble ahead. When Frollo sends the hunchback out to do his bidding by abducting the gypsy girl who has enchanted him, Frollo's motif can almost be heard sending Quasimodo's on its lumbering way. Yet later in this same cue, Phoebus (Alan Marshal), the captain of the guards who rescues Esmeralda from the hunchback and then seeks her attentions for a night of tender debauchery, is given a swashbuckling theme worthy of Korngold (and one Newman was to re-use in Prince of Foxes a decade later and The Robe even later). Finally there is the plainly pious, ever-mystical and always comforting Ave Maria generally credited to sixteenth-century composer (and ordained priest) Tomás Luis de Victoria, its first instrumental rendition in this suite heard at the start of Thank You Mother of God and used to symbolize the sanctuary that Notre Dame represents for society's misfits, including Esmeralda, Quasimodo and, until murder, lust and vengeance completely overtake him, the much-troubled Frollo. In fact, one reason Frollo's motif is able to enter so innocently onto the scene is because it literally steps out of the Ave Maria.

Newman was seemingly inexhaustible in coming up with themes and motifs, but what lifts The Hunchback of Notre Dame score above so many others is their rigorous development as the film unfolds. For instance, in the cue Esmeralda Walks up Steps, written for the fantastic scene in which Esmeralda shows pity on the hunchback on the pillory and, before an astonished mob, brings the unfortunate soul water to drink, Esmeralda's theme — previously sensuous and comely as she lusts for the captain of the guards near the end of Thank You Mother of God — suddenly re-appears here as something serene, deliberate, even holy, reflecting in some respects the qualities of mercy she herself has earlier prayed for so fervently to the Virgin Mary. In this same amazing scene, captured both in the cue Whipping (ultimately trimmed from the film itself but rescued for this re-recording by music reconstructionist John Morgan) as well as Esmeralda Walks up Steps, composed for Quasimodo's punishing public exposure after being flogged, a more resolute version of Frollo's curious motif appears, reflecting not only how severe and inhumane the high justice's notions of law and order truly are, but also his own hidden responsibility for Quasimodo's horrible time on the pillory. Thereafter, the hunchback's own lumbering motif re-appears, again burdened by strange harmonies, as Quasimodo stumbles in torment from the pillory to the cathedral, urged on by Esmeralda's theme. In the final seconds of this scene, as Quasimodo collapses inside the cathedral and out of the crowd's glare, Frollo's motif sounds once more on the alto flute, albeit in a very cool manner. Ultimately, though, Esmeralda's influence triumphs, wonderfully interwoven with a fragment of the pitiful hunchback. A few subtle comments from the timpani bring this incredible sequence to an end.

Too many instances of this fluid and inventive development occur in The Hunchback of Notre Dame to be mentioned here. In the first part of the cue A Woman Has Bewitched Me, Frollo's obsession with the gypsy girl and admittance of it in the church find, in the score, Esmeralda's thematic presence twisted way out of proportion and Frollo's own motif now driven by desperate urgency. Only the church's presence, represented by the Ave Maria, once again stands unbowed. Later, in Esmeralda in Bell Tower, Esmeralda's gratitude to Quasimodo for rescuing her from the hangman's noose (set by mad Frollo) is lovingly chronicled, but so is her pining for the honest and sincere poet Gringoire, whose own love she has come to appreciate almost too late. (And listen for Quasimodo's motif in this cue, trying to step forth from its lowly ranks by literally moving up the hierarchy of woodwinds, though to little avail.) But rating special mention is the film's pull-out-the-stops climax involving the beggars' efforts to storm Notre Dame to rescue Esmeralda, and Quasimodo's response to what he, in deaf ignorance, assumes is an ugly mob set upon hanging her. In the cue Clopin Calls Charge, as the mob gathers and marches defiantly to the cathedral where, ironically, Esmeralda waits in safety, the beggars' theme is heard in a truly rousing rendition. However, once Quasimodo sets about bombarding the mob below with beams and massive blocks of stone and, later, waves of molten metal, the beggars' theme becomes more desperate in the face of the hunchback's motif. These mix wildly with Victoria's Ave Maria and brief snippets for Frollo and Esmeralda, ultimately creating the kind of excitement one finds in works such as Beethoven's Wellington's Victory and Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture. By the time Clopin on Ground arrives, the music paints a well-intentioned mob quelled and its leader down and dying but also a bright future for Esmeralda and her poet-lover. Only a brief but meaningful moment is given over to the hunchback, now doomed to remain in his lonely world among the gargoyles high atop Notre Dame.

Thanks to its abundance of musical ideas and richness in variation and development, the score for The Hunchback of Notre Dame triumphs even when heard away from the film. Nevertheless, some wonderful touches are best appreciated, at least initially, in the context of the film. In the final seconds of Thank You Mother of God, when the poet Gringoire and the handsome soldier who has just rescued Esmeralda are discussing the gypsy lass, Gringoire's puffed-up and false claim to her affections causes him momentarily to lose his footing on a loose rock, his fall wittily accompanied by a slightly discordant, sharply abbreviated mention of Esmeralda in the score — a touch Richard Strauss would have smiled at. Later, during the exciting battle scene between Quasimodo and the mob far below, the hunchback's sudden notion of dumping molten metal on the attackers is accompanied by a deliciously wicked squeal of delight at the very idea from the E-flat clarinet, immediately setting Quasimodo's motif on its determined way again — a bit that might be overlooked by most, yet serves to prove again the many joyful moments that make up this thoroughly enjoyable score. Interestingly, Strauss himself had resorted to the E-flat clarinet for a similar moment of dark humour in the spirited Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks 44 years earlier.

From the very beginning, expectations soared high for the Hunchback score. Arthur Morton, whose remarkable career in Hollywood stretches from the 1930s to his famed partnership as orchestrator for film composer Jerry Goldsmith well into the 1990s, more than once delighted in recalling his unwitting run-in with Newman over the Hunchback score. In 1939 Morton was quietly asked to provide a temporary sound-track for Hunchback for early screening purposes. RKO executives were tickled with the results, he remembered, but Newman became most irritated because Morton temp-tracked the sprawling picture with favourite classical selections rather than more conventional, easier-to-grasp cues from RKO's music library. "I got brand new recordings of Vaughan Williams's F minor Symphony, a couple of Stravinsky pieces — The Firebird and something else — and some Shostakovich plus a bunch of harp glissandi stuff from the RKO library," Morton said in a spirited 1996 interview on occasion of the recording at hand. "And, of course, Alfred was mad as the dickens. He gave me hell about it, too, because he said it made it that much harder for him. Of course, his own score fit it marvellously. Now, what I did I guess sounds presumptuous but, well, I had to have something to go by. I think I even used a couple of things from King Kong. It at least fit it well enough for a preview!"

Some intrigue over The Hunchback of Notre Dame score revolves around Austrian composer Ernst Toch, by 1939 trying to eke out an existence in Hollywood after fleeing the Nazi menace in Europe. (Seventeen years later he would claim a Pulitzer Prize with his third symphony, scored for orchestra and, for a few ear-catching sections, something called a "hisser.") Sources ranging from Louis Kaufman, legendary studio violinist involved in the Hunchback of Notre Dame's autumn 1939 recording sessions, to latter-day film-music researcher William Rosar have insisted Toch wrote some music for the film, notably the exhilarating, Handel-like Hallelujah choral sequence, which bursts forth as Quasimodo swings down from his perch, rescues gypsy dancer Esmeralda from the scaffold and hurries her off into the sanctuary of Notre Dame cathedral. "There's no debate," Rosar has said of Toch's hand in composing this latter sequence, re-used to great effect in Newman's moving scores for The Song of Bernadette (1943) and The Robe (1953). "The facts are fairly unequivocal, supported by manuscript evidence in the case of Toch, and I think there's little doubt that a few parts of the score were ghosted by Robert Russell Bennett." Rosar, pointing to Toch sketches in the Alfred Newman collection at the University of Southern California (as well as remarks in a note by Toch to Newman about working on the Hallelujah, also in the collection), has referred additionally to personal correspondence dated 28th November, 1976, in which Newman colleague Hugo Friedhofer backed up recollections by Newman friend and orchestrator, Eddie Powell, concerning Toch's involvement: "Regarding the perennial Hallelujah — Powell was correct. It was part of a great deal of music which Toch wrote for Hunchback. The rest of it, Alfred either didn't dig or else disliked intensely."

Although music scholar Fred Steiner — easily the foremost expert on Newman's music from this period — has acknowledged the existence of the aforementioned, controversial Hallelujah sketch, he has also termed ultimate authorship of this famous, minute-long sequence an "open question." Did the sketch actually originate from Toch or was it dictated to Toch by Newman for further development, as was custom then? And did Newman later rework Toch's sketch for inclusion in the film, enough so that it became a piece owing far more to Newman than Toch? Although some bars in the sketch usually credited to Toch reportedly echo the Hallelujah heard so gloriously in the film, Steiner has noted that the final version in the film shows significant changes. Until firm evidence surfaces concerning authorship one way or the other, efforts to wholly or even partially credit Ernst Toch for the Hallelujah are, to hear Fred Steiner, "pure speculation." That notwithstanding, Toch's grandson Lawrence Weschler again credited his late grandfather with writing the Hallelujah in a piece published by Atlantic Monthly in December 1996, suggesting that, among the Toch family anyway, authorship of the cue is a foregone conclusion.

Toch's depth of involvement in The Hunchback of Notre Dame has long tantalized researchers, even while works known for certain by Toch have gone unperformed for years. Studio violinist Louis Kaufman, in a lively 1992 interview with Matthias Budinger, was among those to recall Toch's involvement in the score: "For a scene when Charles Laughton as the hunchback is seen climbing up Notre Dame, Toch wrote a fugal treatment of his theme. It was a 10- or 15-minute cue. We needed one day to record this. But Laughton refused the music since his grunts of effort couldn't be heard! So they had no music at all, which killed the excitement of the long climb." Fred Steiner's own research through others, including Newman's brother Emil and orchestrator Robert Russell Bennett, strongly suggests Toch may have written other music for the film, ultimately to see it either reworked or discarded by Newman because it did not fit idiomatically.

Even so, Newman may well have turned over some materials to talented orchestrators such as Eddie Powell and Robert Russell Bennett for extensive development. With a fast-approaching deadline, Newman used a virtual army of talented orchestrators. Clifford McCarty's tireless research on score materials shows that, just in the first part of the score, Powell handled the main title, In the King's Box and Esmeralda's Dance, Bennett (a talented but ridiculously neglected composer in his own right) worked on The Gypsies, Conrad Salinger tackled The Festival and Leonid Raab took The Dance of Death (the latter serving as musical accompaniment for a play mounted during the festival). Salinger and Raab are credited with much of the arranging on the Notre Dame battle sequence, and Steiner says he would not be at all surprised if Bennett contributed much creatively to it. As for the carnival sequence's "Festival of Fools," with all its visceral tonalities, Steiner has said while Newman seldom wrote music in that style, he was hardly a stranger to pungent polytonalities in the late 1930s (and, for what it's worth, the cue was revised and used in Newman's sterling score for Prince of Foxes a decade later). In fact, Newman maintained a friendship with composer Arnold Schoenberg — one that developed to the extent Newman, in a gesture of personal and professional admiration, in 1936 sponsored and produced the very first integral recording of Schoenberg's string quartets. Likewise, Arthur Morton — working at RKO at the time with Newman — has described the composer as well-versed in all styles and techniques in the late 1930s. However, Morton added, extensive work was routinely distributed to everyone in the music department because of ever-pressing deadlines, especially on huge pictures such as Hunchback: "Alfred would try to write all the music when he had the time, but time was always of the essence."

In any case, little contention exists on either side about most of the Hunchback music — Newman was definitely the chief composer. To hear film music archivist John Morgan, who arranged much of the score for the première re-recording at hand, the evidence simply re-affirms Newman's almost peerless gift for crafting full-blooded themes, his deep faith in most of his music associates' talent (and his rare ability to recognise such talent), his long-standing belief in teamwork at all times and, finally, his devotion to doing whatever was right for a picture, and doing it on time. Certainly, the practice of studio composers and arrangers working together in such fashion, and always under the watchful eye of the music director, was hardly unique in the 1930s and 1940s. "To the contrary, it was quite typical of the time," William Rosar said. "Newman routinely got help from others, but the scores were still, by and large, his work." Of hearty collaborations in the realm of film music, Fred Steiner has added knowingly: "It didn't just happen in the 1930s, '40s and '50s, either. In fact, it's still going on today!"

Happily, such matters need not keep one from enjoying this masterful score — and the score did prove winning, beginning with executives at the top. One of Arthur Morton's happiest memories in the business involves Newman at one point sitting down at a piano on an empty sound-stage and performing the score's most infectious themes for RKO producer Pandro S. Berman and his secretary. "And they swooned," Morton recalled. "Now, Alfred, being an astutely pragmatic man, played that lovely theme for Esmeralda over and over, that and the poet's soul theme. Alfred was a great salesman. You know, I don't think anyone was better suited for film music than Alfred."

And despite the fact Newman had earlier scolded Morton for temp-tracking the film with classical pieces, Newman shrewdly zeroed in on Morton's wonderful notion of using the last part of Victoria's Ave Maria to reflect the almighty influence of the church in Hunchback and even employed its choral version for the main title. While Fred Steiner was later prompted to laugh good-naturedly at the utter incongruity of using this particular Ave Maria — after all, The Hunchback of Notre Dame is set a century before Victoria flourished — the film music scholar agreed it fit the picture perfectly. So does the text, which wonderfully mirrors much of what poor Esmeralda herself prays for in the film: "Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death. Amen." (Hugo Friedhofer, ever the wit, once quipped that the perfect score for The Hunchback of Notre Dame should be "quasi-modal.")

Critics have praised RKO's The Hunchback of Notre Dame as one of the finest examples of studio expertise ever. The studio system was one Newman thrived in, most significantly during his twenty years at 20th Century-Fox. Tellingly, after that system fell into decay at the end of the 1950s (hastened by a disastrous musicians' strike), Newman left 20th Century-Fox rather than preside over further gutting of its music department. In the decade that followed, he continued to show vivid talent in such scores as The Greatest Story Ever Told, How the West Was Won and Airport, though friends such as Fred Steiner note he continued to lament the passing of those days when studio music departments thrived and often triumphed, even in the face of crushing deadlines and musically ignorant studio heads.

Bill Whitaker, 1997